Group Karma - It’s Nothing Personal

In December 2012, I was in Japan for second level minister ordination called Kyoshi. We practiced chanting, rituals and etiquette but we were also able to attend lectures on Buddhism by some of the leading Japanese Buddhist scholars.

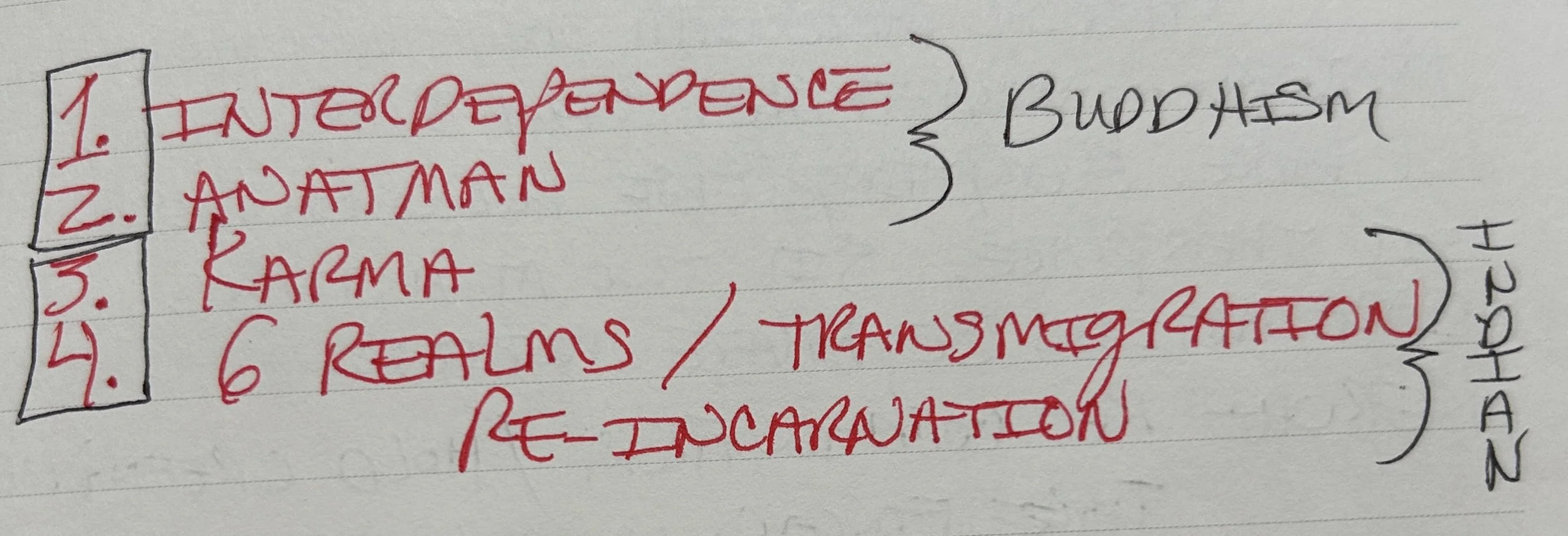

One of these lectures covered the four main teachings of Buddhism:

1. Interdependence

2. Impermanence (Anatman)

3. Karma

4. Transmigration

Here are my notes from that day:

The professor said that the first two are uniquely Buddhist while the second two predate Buddhism. Karma and transmigration were part of the spiritual background of the Buddha’s time. Thus, the Buddha had to address these teachings within the Buddhist context of interdependence and impermanence. Often times the Buddha would use the traditional language of karma and transmigration in order to reinterpret them as something that is flowing in the “here and now” rather than being fixed in the “there and then”.

The problem is that all four of these teachings arrived in China at the same time so they were all given equal emphasis as they are in America. Compounding the problem is that karma is a very ancient concept with many different interpretations. In India, karma was often explained as if it was some sort of moral currency. In effect, you had a personal karma bank account. When you behaved well your balance went up and when you did not then withdrawals were made. The goal was to just stay in the black whenever possible. This was intended as a metaphor but became interpreted literally.

In America, the notion of karma also has an overlay of Christian morals and ethics. I often hear this type of thinking within popular cultural. For example, on TV, whenever someone gets into a car accident they often attribute it to having bad karma, a sort of moral and ethical retribution system for previous bad acts, it is the universe getting even with you.

From a Buddhist perspective, I would describe Buddhist karma as the circumstances that are created for you and your life. Some are of your own doing but the majority is not. This is because another aspect of karma is that there are two kinds of karma. One is personal karma and the other is group karma. When I hear discussions of karma it is almost always about our personal karma. I think this is because Americans are very individualistic and we prize free will. We want to believe we can control our own destiny. We can, but only up to a point.

Personal karma is the way we treat others and the way we see the world. Through practice we can develop new habits of behavior. We can also change the direction of our lives by simply associating with a different group of people. For example, the Buddhist Sangha is a perfect place to change the circumstances of our lives by developing new habits.

But group karma is much different and is often ignored. Our group karma is when we were born, where we were born, the language we speak and the country we live in. It also includes the circumstances of our upbringing. For example, the death of a loved one can change our circumstances in an instant. We cannot really behave our way out of these situations. They are just so much bigger than we are. For example, living through World War Two would be such a defining event.

Our group karma is when we were born, where we were born, the language we speak and the country we live in.

We have to find another way to deal with group karma. We may not be able to behave our way out of these circumstances but we can transcend them. This is possible due to the first two teachings of the Buddha listed above. Group karma is ultimately interdependent and impermanent. Bad times do not stand alone in an eternal isolation from reality itself. Even the bad things in life are not fixed or permanent. We often focus on the transient nature of our youth and health but bad things also fade due to the processes of interdependence and impermanence.

To the American ear, personal karma is something positive, something we have control over and can change. While group karma sounds pessimistic and somewhat defeatist. But as Joseph Campbell says, this is not the only conclusion you could draw from group karma. Seen in a positive light, group karma means that you are not a victim, it is not your fault. Things did not go wrong because you simply did not try hard enough.

Tara Brach, an American psychologist, author, and proponent of Buddhist meditation, observes that we choose guilt and self-blame in order to protect and preserve an imagined sense of self-control. We prefer to embrace personal karma as a form of self-help rather than transcending our group karma by accepting that what we actually control in our lives is quite small. Personal karma is still worth some attention but not at the expense of abandoning all hope of finding new meaning within the events of our lives. We may not be able to practice them away but we can reimagine them as something deeply spiritual and transformative. Your circumstances may not change but your appreciation of them does.

Namuamidabutsu, Rev Jon Turner